TSCA Section 21 has long been a tool used by environmental groups to urge the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to further regulate chemical specific issues under EPA’s TSCA authority. But recently, industry has begun to utilize this provision to push EPA in the opposite direction. This article will explore some historic and recent trends in TSCA Section 21 usage and discuss how it may be utilized moving forward.

TSCA Section 21

TSCA Section 21, 15 U.S.C. § 2620, authorizes “[a]ny person” to petition EPA “to initiate a proceeding for the issuance, amendment, or repeal either a rule under” TSCA Sections 4, 6, or 8, or an order under TSCA Sections 4 or 5(e)/(f). Petitions must “set forth the facts which it is claimed establish that it is necessary to issue, amend, or repeal a rule under” the aforementioned TSCA sections. 15 U.S.C. § 2620(b)(1). EPA is required to act on a petition within 90 days of the petition’s filing.[1] If a petition is granted, EPA must “promptly commence an appropriate proceeding”, 15 U.S.C. § 2620(b)(3), the scope of which is determined by the request in the petition. If the petition is denied, the reasons for denial must be published in the Federal Register. Id. EPA’s denial of a petition is subject to judicial review, if the petitioner so chooses.[2] 15 U.S.C. § 2620(b)(4).

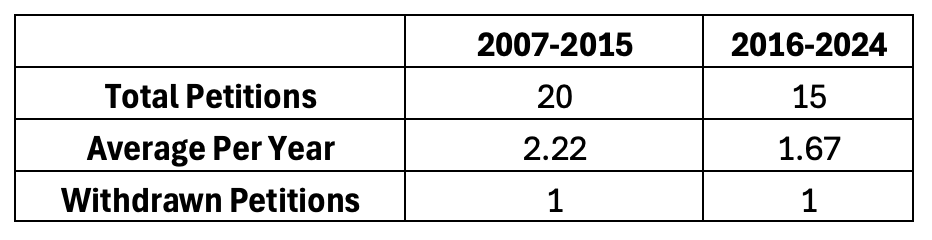

From 2007 through 2024, approximately 35 Section 21 petitions were submitted to EPA.[3] While the 2016 Frank R. Lautenberg Chemical Safety for the 21st Century Act, better known as the Lautenberg Amendments to TSCA, may seem a natural inflection point in Section 21 petition usage (as it gave EPA more rulemaking tools and responsibilities), the numbers show that the average petitions filed per year decreased from 2016-2024 as opposed to 2007-2016:

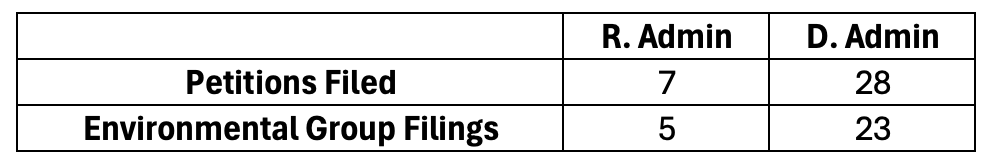

Additionally, fewer petitions were filed per year during Republican administrations than Democratic, and the vast majority of petitions were filed by environmental groups requesting EPA promulgate additional regulations:

Of those seven petitions not filed by environmental groups, five were filed by concerned citizens seeking further chemical regulation and one was filed by a coalition of states seeking promulgation of a rule to increase asbestos reporting requirements. Only one petition, filed in October of 2014, was filed by an industry group, which sought a partial exemption for “biodiesel” from TSCA Section 8 Chemical Data Reporting (CDR) requirements. As a nascent industry in 2014, and one aligned with the then Obama administration’s priorities of renewable energy, it makes sense why a limited reporting exemption was sought by industry at that time.[4]

2025 Information to Date

2025 has been vastly different. Thus far, nine months into the year, there have been six petitions filed, approximately four times as many as the preceding 8-year average and three times the annual average since 2007. Of those six petitions, four of them have come from industry or industry groups seeking amendment or reconsideration to rules finalized under the Biden administration.[5]

Further, of the six petitions filed in 2025, four of them have been withdrawn before EPA could reach a decision, more withdrawals than the preceding 18 years combined. Three of the four withdrawn petitions have been industry-led.

Analysis

For the first time since 1976, the year TSCA was enacted and Section 21 was codified into law, industry is now utilizing TSCA in an offensive way to attack their regulatory burden. It is perhaps unsurprising that industry and the regulated community have not used Section 21 more frequently, as TSCA was relatively toothless prior to the Lautenberg Amendments and the first risk management rules were not finalized until seven years later. Further, the Lautenberg Amendments were a long-negotiated compromise between the various stakeholders and ideologies, kept deliberately vague to permit discretion in application and secure the necessary congressional votes to pass.

But there also appear to be some unique dynamics at play between the Trump administration and industry, where these petitions are being used to signal the administration which regulations to address first. For example, on April 30, 2025, Alliance for a Strong U.S. Battery Sector and Microporous, LLC (collectively, “Petitioners”) filed a Section 21 petition requesting EPA amend the December 17, 2024 final risk management rule for trichloroethylene (TCE Rule) (89 FR 102568). The Petitioners argued, in part, for amending the regulations to include a higher interim existing chemical exposure limit (“ECEL”), which would make personal protective equipment use unnecessary for battery-separator manufacturing operations.

But Petitioners withdrew the petition on July 25, 2025, perhaps because EPA, in a May 27, 2025 sworn declaration filed with the Third Circuit Court of Appeals in TCE rule-related litigation, stated that the Trump administration intended to reconsider the TCE rule, including the ECEL with which the Petitioners took issue.

By way of another example, on May 2, 2025, a coalition of unnamed chemical companies “directly impacted by the reporting requirements of 40 C.F.R. Part 705” (collectively, the “Coalition”) petitioned EPA under TSCA section 21 to amend Part 705. Those requirements were first proposed on June 28, 2021. 86 FR 33926. They are specific to per-and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) and are authorized by the 2020 National Defense Authorization Act (which amended TSCA section 8(a)(7) to require PFAS reporting and recordkeeping regulations). Part 705 mandates that persons who manufactured or imported PFAS or PFAS-containing articles for commercial purposes at any time since January 1, 2011, conduct certain reporting and recordkeeping activities for each year since. The Coalition argued, however, that EPA impermissibly excluded typical TSCA Section 8(a) reporting exemptions from the rule, imposing costly burdens on small businesses and thousands of others without “tangible benefit.”

In either a surprising coincidence or equally surprising bout of government efficiency, EPA delayed PFAS reporting deadlines on May 12, 2025, ten days after the petition was filed. While not addressing Petitioners or the petition itself, EPA issued an interim final rule delaying the start of the submission period from July 11, 2025, until April 13, 2026. EPA justified the delay partly because EPA “requires more time to prepare the reporting application to collect this data.” Somewhat cryptically, though, EPA stated in the announcement that it was “considering a separate action to reopen other aspects of this rule for public comment.” Petitioners withdrew their petition just four days later.

Rather than acting on the petitions themselves, the Trump administration appears to be reading industry signals and acting quickly in response to delay implementation of the challenged rules. The informal response, purportedly taken within the scope of existing federal regulatory authority, and subsequent withdrawal of the petitions achieves not only industry goals but also has the benefit of (1) limiting the scope of potential judicial review, and (2) leaving less of an administrative record upon which challenges can be built. The withdrawn petition can then be refiled as needed and EPA can consider it anew at that time, creating pretext for further regulatory changes. As we approach additional compliance deadlines for the risk management rules and reporting rules finalized under the Biden administration, it would not be surprising if more industry-led TSCA Section 21 petitions were filed and informally acted upon by the current administration.

TSCA Section 21 Moving Forward

Moving forward, we will most likely see continued use of TSCA Section 21 by industry and the regulated community. As discussed above, these petitions allow industry to signal friendly administrations about their preferred changes to regulations in a way that provides a vehicle for government action. They also provide an administrative process for challenging final TSCA rules, such as those that deviate in important ways from proposed rules and in ways industry could not have anticipated when commenting on the proposed rule. This use of TSCA Section 21 has the potential to decrease litigation costs for impacted stakeholders and, perhaps more importantly, potentially limit the scope of judicial review in any subsequent proceeding.

One facet that will need to play out in court is whether or how the denial of a petition seeking modification to existing rules to loosen regulatory requirements can be appealed to a U.S. District Court. As mentioned above, the statutory language appears to primarily contemplate petitioners seeking further regulation of chemical substances, requiring petitioners prove in the District Court that, in varying procedural settings and among other things, EPA has insufficient information “to permit a reasoned evaluation of the health and environmental effects of the chemical substance to be subject to such rule or order” or that the substance may present an unreasonable risk to health or the environment. Those requirements seem incompatible with a petition seeking amendments loosening regulatory requirements.

Contact

For more information about TSCA Section 21, please contact author Wade Stephens, who can be reached at wstephens@lssh-law.com. Paralegal Sasha Burton was also instrumental in performing research for this alert.